Jean-Michel Basquiat transformed chaos into kingship, using raw, crown-laced canvases to center Black brilliance and redefine the language of contemporary art.

Jean-Michel Basquiat transformed chaos into kingship, using raw, crown-laced canvases to center Black brilliance and redefine the language of contemporary art.

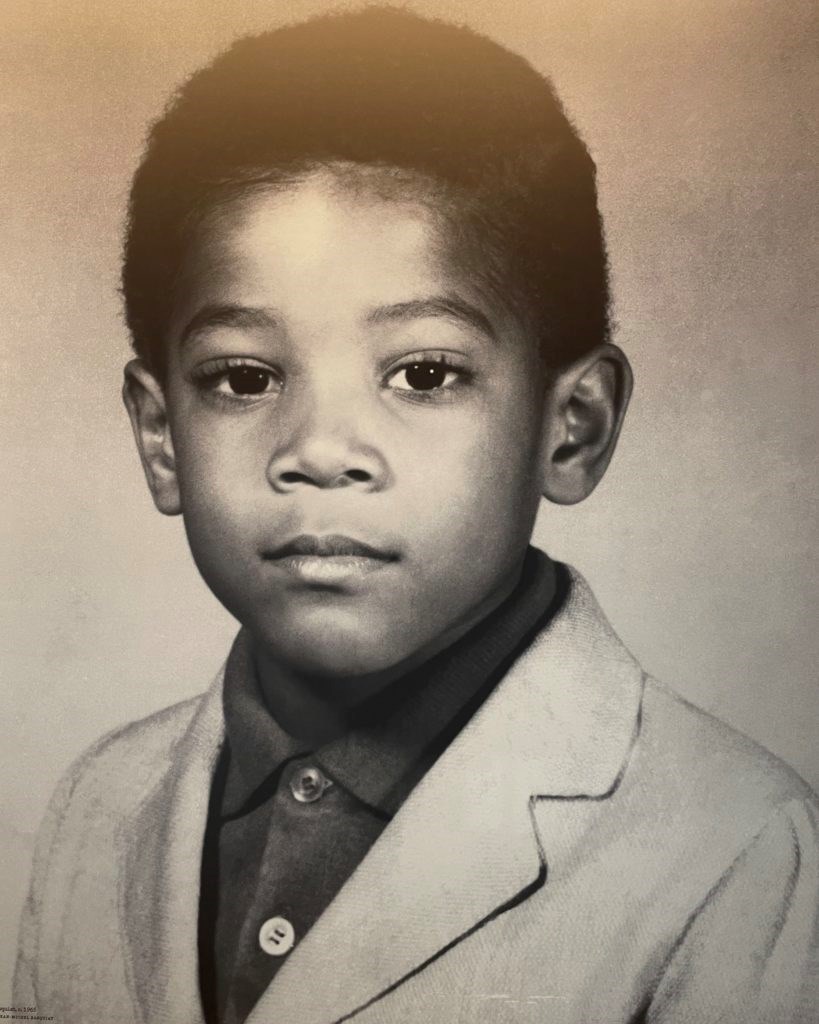

Jean-Michel Basquiat was born in Brooklyn in 1960 to a Haitian father and Puerto Rican mother. From childhood, his world was already multicultural and multilingual as French, Spanish, and English swirled in his home. His mother, Matilde, encouraged his creativity, taking him to the Brooklyn Museum and MoMA while he was still a child. But an accident at age 7 changed everything.

After being hit by a car, he was hospitalized for weeks, passing the time with a copy of Gray’s Anatomy that his mother gave him. The book’s skeletal diagrams and medical sketches imprinted on his imagination, and decades later, bones, skulls, and anatomical fragments would become signatures of his art.

Basquiat never took the straight path. He dropped out of high school at 17, living briefly on the streets, selling hand-painted postcards and T-shirts. But downtown New York was his canvas. With friend Al Diaz, he created SAMO©, a graffiti persona that filled SoHo walls with cryptic epigrams:

“SAMO as an end to mindwash religion.”

“SAMO as an end to playing art.”

These weren’t vandalism, they were poetry. They earned him a cult following in the late ’70s, and by 1980, critics were calling him the graffiti poet of the Lower East Side.

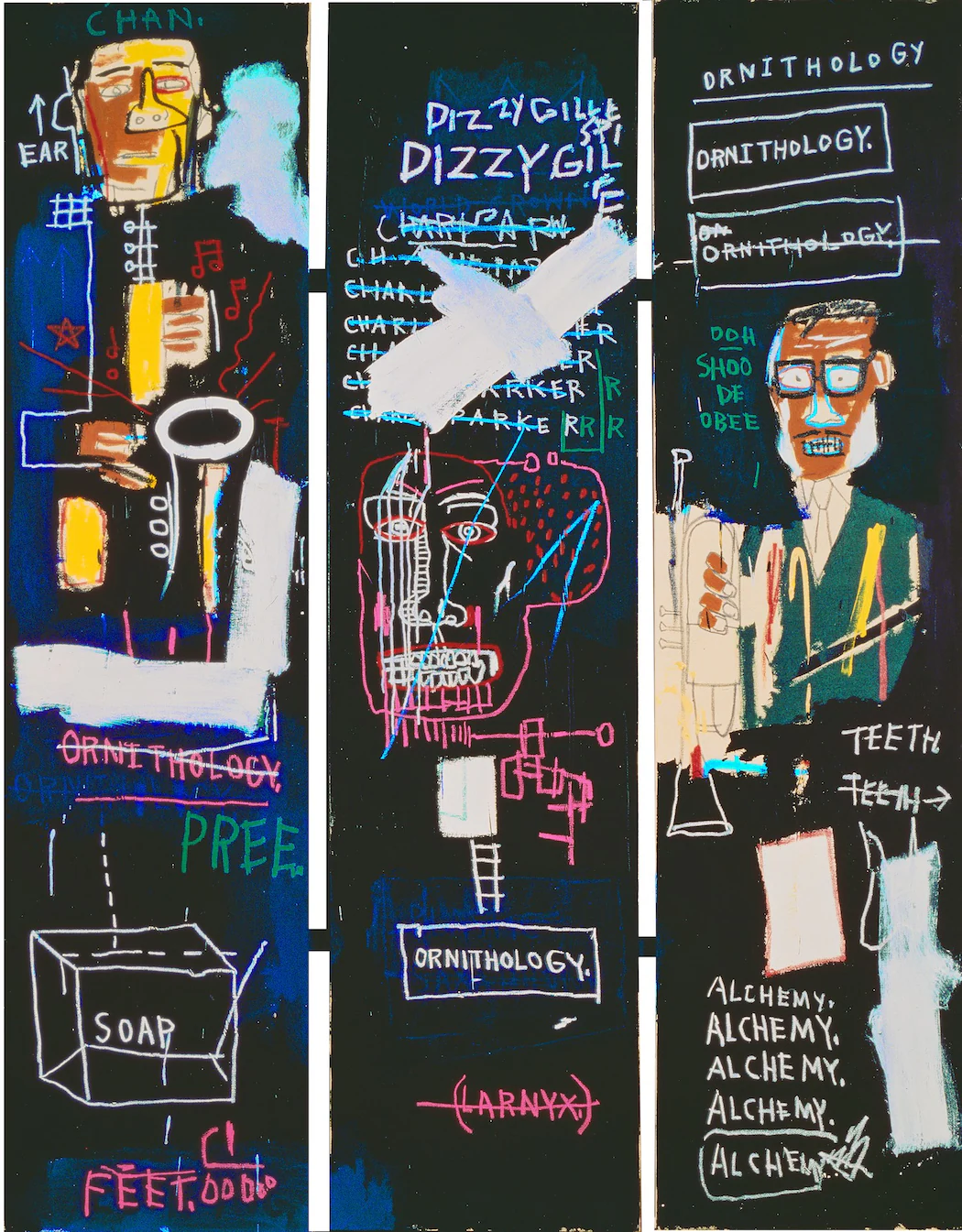

When Basquiat shifted to canvas, he brought the street’s urgency with him. His works were explosive featuring scribbled text, anatomical sketches, crowns, saints, and jazz references colliding in neon and acrylic.

They looked chaotic, but the chaos was intentional. His approach was improvisational, like the bebop jazz he loved. Fast, layered, and unpredictable.

Robert Hughes once described his work as carrying “the raw energy of a subway wall”. Yet within the frenzy was sharp commentary: about history, race, wealth, and power.

Basquiat’s art didn’t just break into galleries; it dragged Black narratives in with it. At a time when Black figures were largely absent from fine art, he painted them as icons.

He crowned jazz legends like Charlie Parker and boxers like Joe Louis, giving them the same reverence museums reserved for European kings.

His iconic three-pointed crown became a visual declaration of Black excellence what the critic Franklin Sirmans called “a reminder of majesty in the face of invisibility”.

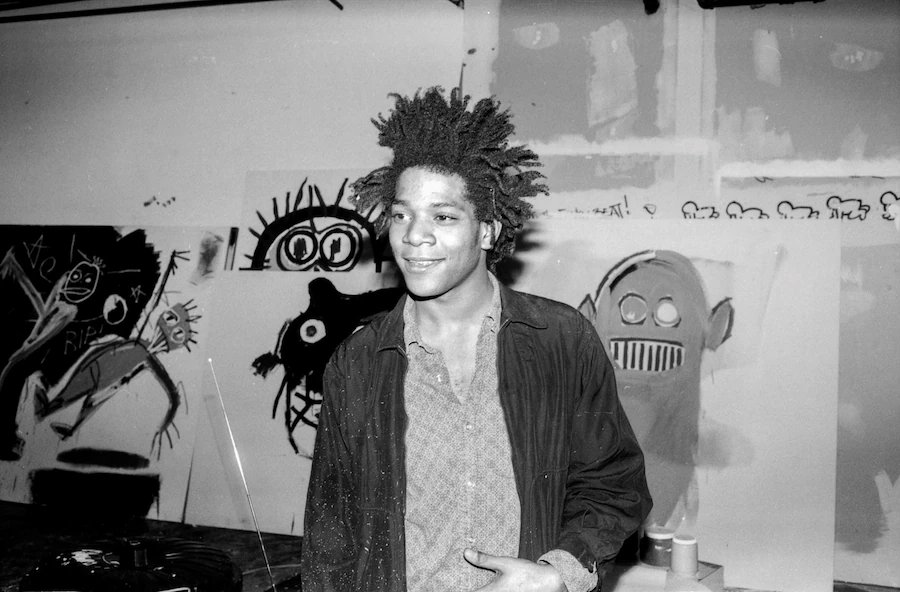

The art world didn’t know how to contain him. Some hailed him a prodigy, while others saw him as an outsider novelty. His collaboration with Andy Warhol amplified both his fame and criticism.

Was he Warhol’s student, sidekick, or equal?

Basquiat resisted every box. He painted fast, lived faster, and carried a sense of both brilliance and tragedy.

As art historian Jordana Moore Saggese notes, he was constantly negotiating between being celebrated and being consumed.

Basquiat died in 1988 at just 27, another member of the “27 Club.” Yet his influence outlived him. In 2017, his painting *Untitled (1982) A* skull rendered in screaming color sold for $110.5 million at Sotheby’s, one of the highest prices ever for an American artist.

But beyond auctions, his fingerprints are everywhere: in Jay-Z’s lyrics (“I’m the new Jean-Michel”), in Asake’s music (”…I’m a work of art Basquiat), in Virgil Abloh’s fashion, in the codes of Banksy and contemporary street art.

He gave permission for rawness to be art, for Blackness to be crowned, for chaos to mean brilliance.

Basquiat wasn’t just an artist; he was a cultural disruptor. He blurred the line between street and gallery, between chaos and composition, between invisibility and immortality.

In today’s world, where questions of race, authenticity, and representation still burn his work feels prophetic.

He didn’t just paint crowns. He handed them out.

Comments